GEORGE STARKMAN HOLOCAUST STORY:Part Ten: Gusen I | ||||

My father, George Starkman was born on October 29, 1917 and died on May 18, 2016 at age 98. Except as noted, these videos were made between 1992 and 1994 with Jay Starkman interviewing. To access a chapter of the video, select it from the list to the left of the video window below. Relevant links for each chapter are displayed to the right of the video window.An HTML5 browser is required to view videos. If your browser is up-to-date, it should support HTML5. |

||||

|

My Dad was the sole survivor of the Holocaust from his immediate family. Many survivors wouldn't talk about the Holocaust until 1993 when Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List made it fashionable. But he always spoke at length about his horrific ordeal. Dad was the eldest of three children from a mixed marriage. His father was a Gerrer chassid and his mother was an Alexander chassid; "shtreng frum" (strictly religious). He was 21 and living in Kalisz when the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939. The Germans murdered his father in November 1939 — drenched with water under a tall water pump in cold November Poland and beaten to death along with several prominent Jews in a mass torture execution. His father's father had been a dayan (religious judge) for 40 years in this city of 30,000 Jews. In December 1940, the Germans sent the remaining Jews of Kalisz to Lublin, transporting them by cattle car, standing room only, for over two days without food or water. This transport included my Dad with his mother, brother and sister. From Lublin, he planned to escape to Russia leading his brother and eight other lads with him. On the morning that his mother woke him to leave, after much agonizing, he changed his mind. He couldn't bear to abandon his mother and sister. Conditions worsened in Lublin so they escaped to Częstochowa. When Yom Kippur arrived in 1942, the Germans forbade Jewish worship. Dad attended a clandestine service. The prayers for mechila were soon answered by Germans bursting into the room, guns blazing. Dad jumped out a window to escape the bullets. A German with a pistol ran after him. "Why and how he didn't shoot me is a miracle," he still wondered until his death. The day after Yom Kippur, the Germans began liquidating the Częstochowa ghetto sending residents, including his mother, to Treblinka, the infamous death camp.

In January 1943, the Germans, packed him and his brother on a cattle car with 150 people for transport to Treblinka. Dad knew what awaited there and as he pushed away the barbed wire from the small opening in the cattle car intending to jump from the speeding train, the other Jews protested, "Vest unz brengen umglik." (You'll bring us misfortune.) He and his brother didn't know about the riflemen posted atop each cattle car. Fortunately, the bullets missed.

There was nowhere else for a Jew to go but trudge 98 km (61 miles) in the snow back to the Częstochowa Ghetto, with no coat as the Germans had confiscated them before boarding the train. They had also demanded removal of shoes, but the Germans didn't notice that Dad and his brother kept theirs. A month after their return to Częstochowa, the Germans shot their 19 year-old sister. As the Germans liquidated the 48,000 Jews from the ghetto in 1942-1943, he and his brother were separated and they were among the 5,000 who wound up in different labor camps instead of Treblinka. He was sent to Bliżyn, then Płaszów where the sadistic commandant riding his white horse (featured in Schindler's List) took target practice on the prisoners.

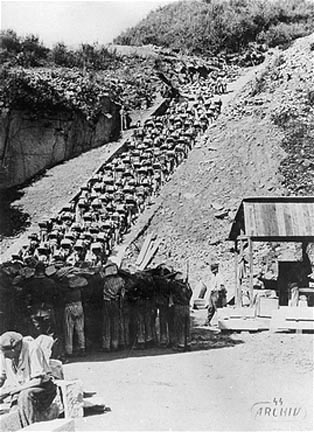

He was sent to the Mauthausen rock quarry. 186 uneven granite "stairs of death" to climb barefoot with no handrail and a 65-100 lb. boulder on his shoulders. Carry a boulder too small and a beating awaited you at the top, and you were forced to carry it down again. Repeat that and you'd get thrown over the "Parachute Wall" cliff into the quarry. Hell soon worsened as the Germans transferred him to Gusen II, considered the most brutal of the Mauthausen-Gusen system. One inmate described it:

Only two percent of Gusen inmates survived. Mauthausen and Gusen were the only Class III camps in the German concentration camp system where prisoners served hard labor. As the war drew to a close, the Germans considered drowning Gusen survivors in the Danube River below. Instead, they death marched them to the Gunskirchen concentration camp. Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945. Berlin surrendered on May 2; Germany on May 7. Dad was liberated by the Americans on May 5. Suffering from pleurisy in his lungs and gangrene in his left knee, in August he was admitted to a hospital in Linz, Austria. A German SS doctor took Dad under his care and came to see him daily before making rounds to see other patients. He remained hospitalized until January 1946. Dad had an uncle who had come to America around 1927. He remembered the address: Jack Heber, 210 West New York, 60th Street, NJ. (It was an old wrongly formatted address. Would that get delivered today?) Mail being what it was in war-ravaged Europe, he received no reply. So, he made plans to emigrate to Palestine with some friends. (They eventually sailed on the ill-fated Altalena without him.) Months later a telegram arrived from his uncle saying that he had replied to each prior letter and that he was arranging to bring him to America. All survivors are scarred by the Holocaust. Among his other scars, the Yom Kippur 1942 experience left Dad unable to regularly attend shul for decades. The nine lads who he was to lead to Russia in 1940 remained in Poland. None survived. Dad has no regrets about not escaping to Russia where he might have avoided the suffering he endured. "I'm glad I stayed because I know exactly what happened to my family. Otherwise, I'd never know and that would have haunted me the rest of my life." Dad, age 98, died on May 18, 2016 from a broken hip and pneumonia, a leg injury and lung disease, 70 years after he left the hospital in Linz following a leg injury and lung disease. There must be truth in the Ten Commandments promise for a prolonged life from honoring father and mother. |