Can Congress Be Bought?

|

Democrats won control of the Senate in the 1932 election and Barry's tenure as sergeant-at-arms would end on March 3, 1933 when the Democrats were seated. In preparation for retirement, Barry arranged to write a series of articles for former New York Governor Al Smith's monthly magazine, New Outlook, for which he would be paid $250 per article. The first article was supposed to be published in the March 1933 issue, but for some unexplained reason, it was printed in the February issue.

Both the House and Senate were immediately outraged by the explosive article, especially the "incredulous" accusation that Congress could be bought. As retribution, the Senate immediately suspended and then fired David Barry just three weeks before he was to retire. Historian Donald A. Ritchie pinpointed Barry's real crime, "as an elected officer of the Senate, Barry had confused his roles and written with an autonomy his position did not offer, no matter how vague his criticisms."

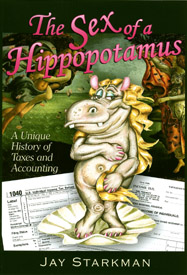

You'll find great stories about making tax sausage in Congress, including the corrupt Huey Long and hero James Couzens who stood up to the Senate bosses in The Sex of a Hippopotamus: A Unique History of Taxes and Accounting.

You'll find great stories about making tax sausage in Congress, including the corrupt Huey Long and hero James Couzens who stood up to the Senate bosses in The Sex of a Hippopotamus: A Unique History of Taxes and Accounting.

You'll only find David S. Barry's controversial article on this website.

Over the Hill to Demagoguery

by David S. Barry

Sergeant-at-Arms, U.S. Senate

New Outlook

February 1933

pp. 40 - 42

Contrary, perhaps, to popular belief, there are not many crooks in Congress, that is, out and out grafters, or those who are willing to be such; there are not many Senators or Representatives who sell their vote for money, and it is pretty well known who those few are; but there are many demagogues of the kind that will vote for legislation solely because they think that it will help their political and social fortunes.

This is what passed the constitutional amendment providing for the popular election of Senators, it is what passed the amendment giving suffrage to women, it is what passed the prohibition amendment, and it is what has made possible the almost successful attempt to hang the bonus on the American taxpayers. There have been progressives, insurgents, and blocs in Congress for many years, but they have not been so effective as in recent years, and as they will be for sometime to come.

*

Forty years ago, for instance, when the conservative Republicans were in control of the Senate and House of Representatives, when the late Senator Aldrich of Rhode Island was the suave but steel-spined boss of the United States Senate, and when his colleagues were such men as Allison of Iowa, Hale of Maine, Platt of Connecticut, Hanna and Foraker of Ohio, Spooner of Wisconsin, there were populist insurgents, and progressives who were able to make trouble, but who did not succeed in actually putting over much radical legislation because they were too few. There was Peffer and "Sockless" Jerry Simpson of Kansas, Allen of Nebraska, Butler of North Carolina, and before them, Weaver of Iowa, a Presidential candidate. They will made a big noise, but they did not accomplish much. Now, however, a large number of this class have been elected to Congress in the recent elections, and the question is, how far will they be able to go?

It is not so many years ago that the elder LaFollette embodied something of the ideas of these men by proposing that Congress have the right to veto the decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States. And reflecting something of this view, President-elect Roosevelt, in the course of the last campaign somewhat contemptuously, if inadvertently and possibly without fully considering seriousness of the question, insinuated that the Republicans in Congress now had the control of the Supreme Court. Mr. Roosevelt, probably, had no intention of going further than to refer incidentally to the political situation which exists, but the reference to the Court was taken seriously enough to cause President Hoover to wrap Mr. Roosevelt over the knuckles in his campaign speeches for even referring to it.

*

Congress, it cannot be denied, is becoming more and more careless of the letter of the Constitution; and more than once in recent sessions of Congress the spirit, if not the precise letter, of this charter has been side-stepped in an effort to enact some legislation plainly violative of the Constitution itself.

It was the late Tim Campbell, of New York, a Tammany Congressman, who had a wide reputation as a wit although he had none of his make-up, who is popularly credited with the saying, "What's the Constitution among friends?" Tim Campbell never said it; he did not have wit enough, but many public men, in Congress and out, have said it many times since Campbell's day, and many more have recognized the point of the question by advocating, and in some cases by enacting, legislation which fifty years ago would have been regarded as an insult to the Constitution, and as a slap in the face to those who believe in respecting and upholding it.

But it is only in recent years that really pertinent questions have come up for discussion and action in Congress which have given rise to the belief that the Constitution stands in the way of the sort of radical legislation held to be for the good of the American people. In short, there are, and have been, in Congress for many years past, those who sincerely believe that it is time not only to amend but to revise the Constitution, and this number has, undoubtedly, been greatly increased as a result of the elections of last November.

*

There are in Congress to-day, and will be, undoubtedly, for many years to come, a powerful and influential group of businessmen and conservatives, but the great mass of Senators and Representatives will be inexperienced men, voted into office by the radical elements of the electorate which is eager for any kind of a change which promises to lift them out of the depression; and the efforts of the conservatives in both parties to hold these wild ones down to sane and sensible legislation, of a kind that may be depended upon to give all classes the kind of relief that will be wholesome and beneficial to them, must of necessity be unremitting.

When Senator Aldrich was in virtual control of legislation in Washington, and, naturally influential in the Republican administration, with which he served, it was his sincere belief, concurred in by many of his colleagues and associates, that the masses of people were not capable of suggesting legislation, because they really did not know what was best for them. He felt that they advocated reforms which would be no improvement on the laws as they stood, and that in the end they would defeat their own purpose. The class of men, however, who felt that way, have now largely been retired from the scene of action. There are a few of them left, it is true, but they are now too few in number to make their influence readily felt, and the so-called leaders in Congress, who uphold their beliefs, are prepared to sit back and give those who have been elected as the representatives of the masses of the people a chance to take the bridle in their teeth and run things for a while to suit themselves.

*

There will be little opportunity in the Congress of the near future for the "conservative" group as those are called who believe in, and are willing to serve, Big Business. It will be the reign of the people for a time and if Senator Aldrich and those who believed with him were right, the so-called leaders in Congress, some of whom are only mildly radical, will not the able to lead very far or to accomplish much. It will be up to President-elect Roosevelt to hold the most radical of the committee chairman in both Senate and House of Representatives in check, and to see to it that the ill-considered unbaked legislative propositions of the fanatical shall be controlled.

*

The committees of Congress are, of course, the places where legislation is really perfected. The rank and file of the parties in either House have little direct influence upon legislative measures after they emerge from the committees where they originate and whence they appear on the floor of the Senate and House. So far as the Senate is concerned the Republicans have been only nominally in control for several years. There have been radical Senators as chairmen of some of the most important committees, but even so, there have been enough conservatives or, as they have been known, administration Senators, because they followed the lead of President Hoover, to keep the majority of the radical bills in committee pigeon holes.

In the days of Aldrich it was quite possible to frame, and to enact legislation, to put through executive nominations, and give direction to the entire policy of Congress without ever consulting any except the conservative class. It may be that in those days there were too many men who knowingly, or all unwittingly, were representing great business interests.

This condition was well illustrated by an incident which occurred on the occasion when there was a vacancy to be filled in the Republican membership on the Committee on Finance, and when a tally was being made that would indicate the number of votes that could be depended upon to put over a certain bill. The chairman, with his lieutenants, one of whom was the late Senator Murray Crane of Massachusetts, was going over the names of the committee members and finally suggested for the vacancy of a Republican Senator from the west who was deeply interested financially and otherwise in the copper industry. He was put down by the chairman as ready to vote "yea," and one of the Senators was unsophisticated enough to inquire whence the knowledge that he would vote that way as he had not been in Washington and no one had ever seen him. "We do not have to ask him," said a smiling boss in his suave and simple matter; "we know what the Amalgamated Copper Company wants, and that is sufficient."

*

The real cause of the failure of the Republicans in the Senate to enact certain legislation in line with the policies of President Hoover is due, of course, to the fact that for the past few years they have been only nominally in control of the Senate. They had a majority on paper, but owing to the large number of progressives or insurgent Senators who were able at any time to upset their plans by cooperating with the Democratic minority, it was impossible for them to unite on any plans and policies of legislation that they could be certain of enacting. Party lines in the Senate have been largely ignored for some time, but of course after the fourth of March the Democrats will be in full control without being under obligations to consult any Senators not in their own party.

But while in full control, the Democrats will have their troubles as will readily be seen when account is taken of some of the same events of the last session. Senator Robinson, of Arkansas, is the duly elected Democratic leader of the Senate. He has been a forceful, broad-minded, and popular leader, but he was probably unprepared for the party split that arose in the closing days of the session by the unprecedented attack upon his leadership, made in open Senate, by a Democratic Senator, Huey Long of Louisiana. Mr. Robinson was plainly taken by surprise but never replied to Mr. Long who subsequently repeated his attack, to the astonishment of the Senate. Whatever Mr. Long's standing as a Democratic Senator may be, he is certainly a fluid and forceful speaker. He came down to the front row of the Democratic side, and in his usual vigorous matter, called the attention of the Senate, and the country, to the serious handicap under which the Democratic party was laboring, because their leadership in the Senate had been committed to a Democrat who represented, not the kind of people who make up the rank and file of the Democratic party, but more the interests of great business. He then proceeded to prove this assertion by reading a list of clients that the law firm, of which Mr. Robinson is the head, were the regular retained attorneys; and the Senate was still more astonished. Mr. Long declined, moreover, to accept the committee assignments given to him by the Democratic caucus, and has since served on no committees.

Mr. Robinson made no reply, although many of his colleagues were not surprised that he did not do so, and later, after the adjournment of the session of the Senate, Mr. Long championed the cause of Mrs. Caraway for the Arkansas Senatorship; and later he made the picturesque and forceful campaign in Arkansas for her, which ended in an easy victory. Mr. Robinson announced later in re-arrangement of his law office connections.

The echoes of that attack upon the Democratic leader in the Senate and the subsequent campaign in the State of Arkansas will probably be heard throughout the coming session of Congress, and what effect it will have on the career of Mr. Robinson, who is popular on both sides of the Senate chamber, remains to be seen.

It matters little now, in view of the results of the recent election, that a later burst of party independence was voiced in a similar way by a similar attack upon the Republican leader, Mr. Watson of Indiana, and one that has perhaps no counterpart, in legislative annals. As Mr. Watson was defeated for re-election in the overwhelming vote for President-elect Roosevelt and the balance of the Democratic ticket in the State of Indiana, he may choose to forget incident in the Senate, and to look upon it all as an incident in the fortunes of war.

It was on the last day of the last session of Congress, and Mr. Couzens had been for many weeks opposing the passage of the Home Loan Bank bill, and had supposed with good reason, he thought, that the Republican leader, Mr. Watson, was with him in his opposition. But as a matter of fact, toward the end of the struggle for the passage of the bill it developed that Mr. Watson was a strong champion of it. Finally, after it had been passed, it was found that no appropriation had been made to carry out its provisions, and so in the closing hours of the last day an effort was made to provide for this oversight. The late Senator Jones of Washington, chairman of the Committee on Appropriations, after a series of conferences, quietly moved to take up a bill that had already passed the House and been reported favorably by the Senate committee, "To provide for the closing of a portion of Virginia Avenue, S.E., and for other purposes." Then it was that Mr. Couzens, after expressing the opinion that, "when the country knows the type of leadership we have had on this side of the aisle, when that permeates in Indiana, I am quite satisfied with what the Democrats will do with the Senator from Indiana." Then he said he resented the kind of tactics that had been employed in the passage of the measure and said, "I want to say to the Senator from Indiana that if he thinks he has made any progress, politically, or as a leader of the Senate, by resorting to these tricks, then he is very much mistaken."

Here Vice President Curtis intervened to say that a Senator cannot accuse another Senator of resorting to tricks, and was asked by Mr. Couzens to define the word "trick." On the chairman's declining to decide the question for him, he declared that the use of the word "trick" is not in violation of the rule unless he could be told what the definition of the word is, and declared that he would stay within the rules, but that he would have the Senate pass upon them, and not the Vice President.

Mr. Couzens then proceeded with his attack upon Indiana Senator and charged that during all the period of time that the Senator from Indiana was chairman of the sub-committee, there was delay, delay, delay, for month after month, and no effort was made even to get the bill out of the committee, until the last few days of the session, and that suddenly he became its leading advocate. Entering a further exchange of compliments, and enter Mr. Couzens had made the remark in warning to Watson that, "If he believes that he is making any progress by endorsing, as leader, this type of legislation in this manner of doing things, he will find that he makes no progress here or elsewhere," the subject was allowed to drop. The appropriation was made as an amendment to the bill to close a portion of Virginia Avenue.

Such incidents as these illustrate the bitterness of feeling existing even among party associates on both sides of the Senate chamber. They give an idea of the kind of "harmony" that may be expected in the coming session, if, indeed, all personal feeling has not been wiped out by the overwhelming defeat of the Republican Party and the large number of its leading Senators, including Mr. Watson, and their retirement to a hopeless minority in the Senate and the passing of control there as elsewhere, to the Democrats.